When a biologic drug hits the market, it doesn’t just come with a price tag-it comes with a legal shield. Unlike generic pills, which can jump in as soon as a patent expires, biosimilars face a maze of patents, exclusivity periods, and legal battles before they can even be considered. In the U.S., the road to biosimilar entry isn’t just long-it’s deliberately constructed to delay competition for over a decade. And while patients in Europe and Japan see lower prices years earlier, Americans often wait until the very last day-or longer-to access affordable versions of life-changing medicines.

The 12-Year Lockdown: How the BPCIA Delays Competition

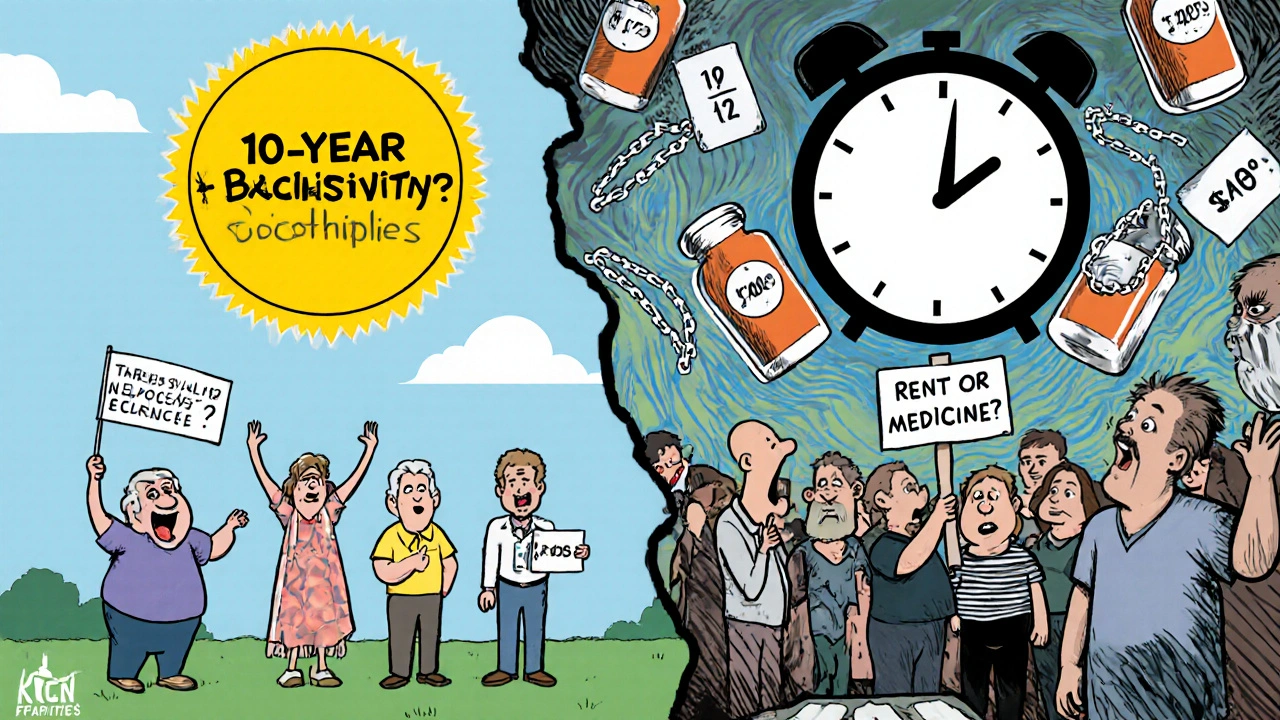

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), passed in 2010, created the legal framework for biosimilars in the U.S. But instead of opening the door quickly, it built a 12-year wall. That’s not a patent expiration date-it’s a full 12 years from the FDA’s first approval of the original biologic before a biosimilar can even be sold. This isn’t just about patents. It’s about data exclusivity. For the first four years, no biosimilar company can even submit an application to the FDA. For the next eight years, they can submit-but the FDA can’t approve it. That’s a total of 12 years where the original drug has zero competition, even if its core patents expire earlier.Compare that to Europe, where biologics get 10 years of data exclusivity plus one year of market exclusivity-11 years total. Or Japan, which offers 8 years of data protection and 4 years of market exclusivity, still totaling 12. But here’s the kicker: in Europe, biosimilars started hitting shelves for drugs like Humira in 2018. In the U.S., they didn’t arrive until 2023. That five-year gap cost American patients an estimated $167 billion in extra spending on just three drugs: Humira, Enbrel, and Eliquis.

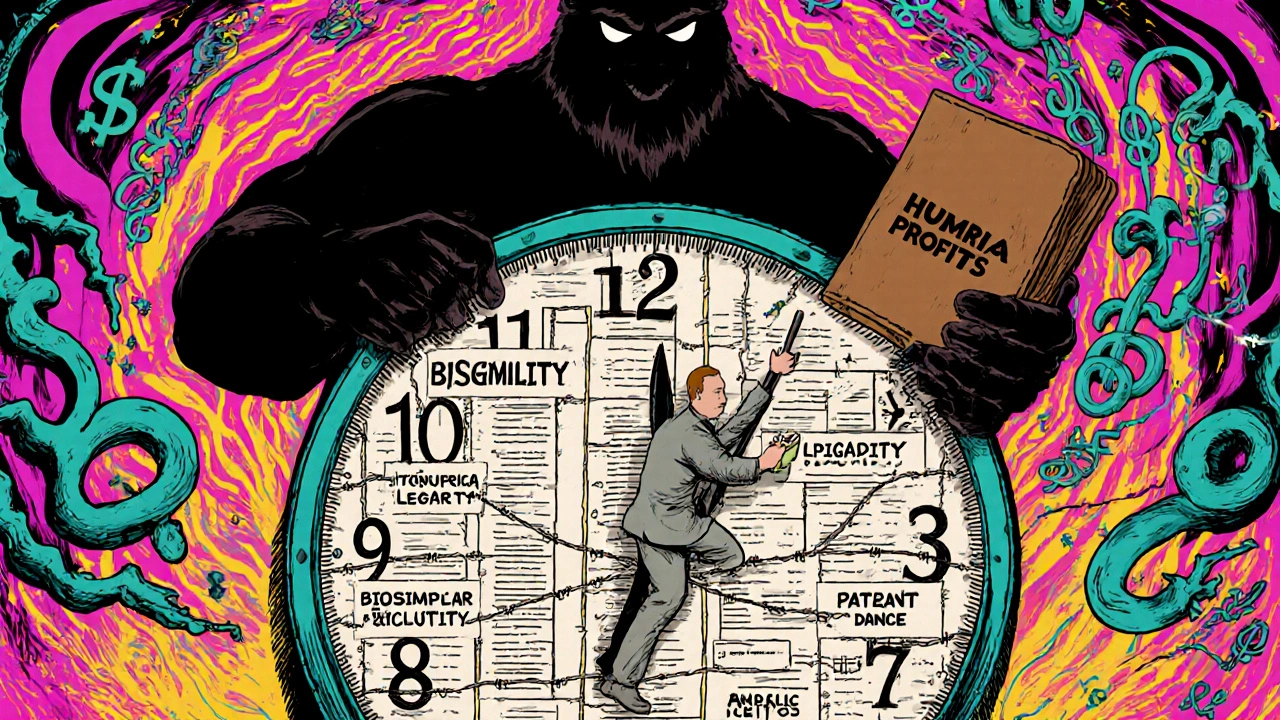

The Patent Dance: A Legal Trap for Biosimilar Makers

Even after the 4-year waiting period, biosimilar companies don’t just file paperwork and wait. They’re pulled into what’s called the “patent dance”-a complex, step-by-step legal exchange between the biosimilar maker and the original drug company. It starts when the biosimilar applicant sends its full application and manufacturing details to the originator. The originator then has 60 days to list every patent they think might be infringed. The biosimilar company has another 60 days to respond, explaining why each patent is invalid or doesn’t apply. Then comes 15 days of negotiation to pick which patents will be litigated.This process sounds fair. In practice, it’s a delay tactic. Big pharma companies pile on hundreds of patents-not just for the drug’s chemical structure, but for delivery devices, manufacturing methods, dosing schedules, even packaging. AbbVie, the maker of Humira, held over 160 patents on the drug, many filed years after the original approval. These weren’t all groundbreaking innovations. Many were minor tweaks designed to stretch protection. The patent dance lets them drag out litigation for years, pushing biosimilar entry past the 12-year mark.

The Supreme Court weighed in on this in 2017, ruling that biosimilar companies don’t have to participate in the patent dance. But most still do, because skipping it opens them up to immediate lawsuits. It’s a lose-lose. Either you play the game and wait, or you get sued and delay even longer.

Why Biosimilars Cost More Than Generics

A generic aspirin costs pennies because it’s chemically identical to the brand-name version. A biosimilar isn’t. Biologics are made from living cells-proteins, antibodies, complex molecules that are hard to replicate exactly. So, a biosimilar maker doesn’t just copy a formula. They have to reverse-engineer a living system. That takes five to nine years and over $100 million, sometimes up to $250 million for advanced therapies like antibody-drug conjugates or cell therapies.That’s 50 to 100 times more expensive than making a generic pill. And it’s not just about money. The FDA requires biosimilar makers to prove their product is “highly similar” to the original-with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency. That means running head-to-head clinical trials, analyzing protein structures down to the amino acid level, and proving the drug behaves the same in the body. It’s science-heavy, time-intensive, and risky. If one batch fails, the whole process can stall.

That’s why only 38 biosimilars have been approved in the U.S. since 2015, while Europe has approved 88. The cost and complexity scare off smaller companies. Even big players like Pfizer and Amgen are selective. They only invest in biologics with high sales potential-like Humira or Enbrel-leaving dozens of others untouched.

The Biosimilar Void: What’s Being Left Behind

Between 2025 and 2034, 118 biologics will lose patent protection in the U.S.-a $234 billion market. But only 12 of them currently have biosimilars in development. That’s the “biosimilar void.” And it’s not random. The biggest gaps are in drugs for rare diseases, cancer, and complex therapies.Take orphan drugs. Over 60% of the biologics set to expire in the next decade treat rare conditions. Only one of those-eculizumab, used for a rare blood disorder-has a biosimilar in the pipeline. The rest? Silence. Why? Because the patient population is small. Even if the drug costs $500,000 a year, there aren’t enough users to justify a $200 million development cost.

And then there’s oncology. Cancer biologics are among the most expensive drugs in the world. But developing biosimilars for them is harder because they’re often used in combination with other drugs, and clinical trials require massive patient groups. No company wants to risk millions on a drug that might not be adopted by doctors who are used to the original.

Meanwhile, the FDA’s 2022 Biosimilars Action Plan promised to improve communication, speed up reviews, and support competition. But two years later, progress is slow. No major regulatory changes have cut the timeline. No new funding has helped small developers. The system is still stuck.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

The big winners? The original drugmakers. Companies like AbbVie, Roche, and Amgen have turned biologics into cash cows. Humira’s price jumped 470% between 2012 and 2022 in the U.S., even as European prices stayed flat after biosimilars arrived. Patients pay more. Insurers pay more. Medicare and Medicaid pay more.Who loses? Patients. Pharmacists. Providers. A 2022 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 63% of pharmacists had patients who quit their biologic treatment because they couldn’t afford it. The Arthritis Foundation documented cases where people chose between rent and their biologic. In cancer care, Dr. Peter Bach of Memorial Sloan Kettering found U.S. patients paid 300% more than Europeans for the same treatment.

And it’s not just about money. Delaying biosimilars slows innovation. When a drug stays expensive, research dollars go toward new, even pricier drugs instead of improving existing ones. Biosimilars aren’t just cheaper-they’re a pressure valve that forces the whole system to get better.

What’s Next? The Road to Change

There are signs of movement. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the U.S. could save $158 billion over the next decade if biosimilars enter faster. That’s real money-money that could cover insulin for millions or fund cancer screenings for underserved communities.Legislation like the Biosimilars User Fee Act of 2022 tried to speed up approvals and reduce fees for small developers. But it stalled in Congress. Without political will, the 12-year clock keeps ticking.

Some states are trying to step in. A few have passed laws requiring pharmacists to substitute biosimilars unless the doctor objects-similar to how generics are handled. But without federal reform, these efforts are scattered and limited.

The truth? The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed-to protect profits, not patients. Until the rules change, biosimilars will keep entering late, sparingly, and too late for the people who need them most.

Tom Shepherd 26.11.2025

The 12-year lock is insane. I get patents, but this isn't innovation-it's legal gymnastics. My dad's on Humira and paid $12k a year before the biosimilar finally showed up. He almost lost his house. No one talks about that part.

Rhiana Grob 26.11.2025

This is one of those issues where policy and humanity collide. We reward innovation, yes-but not at the cost of human dignity. The data exclusivity period should be tied to actual therapeutic advancement, not patent stacking. Patients aren't balance sheet line items.

Frances Melendez 26.11.2025

Big Pharma is just another greedy corporation and we let them get away with it because we're too lazy to care. People are dying because they can't afford their meds and you're all sitting here debating legal loopholes like it's a board game. Wake up.

Rebecca Price 26.11.2025

It's ironic that we celebrate medical breakthroughs but punish access to them. The FDA's Biosimilars Action Plan sounds good on paper, but without enforcement, it's just PR. Maybe we need a public advocate for biosimilar access-someone whose job is to cut through the red tape.

shawn monroe 26.11.2025

Let’s break this down: biosimilars aren’t generics-they’re biologics, which means they’re complex protein structures with post-translational modifications, glycosylation profiles, and tertiary conformations that require analytical characterization at the ppm level. The development cost isn’t just high-it’s biophysically intensive. And yeah, the patent dance is a nightmare. AbbVie’s 160 patents? That’s not innovation-it’s litigation arbitrage. But the real bottleneck? The FDA’s review capacity. They’re understaffed, underfunded, and drowning in INDs. Fix that first.

marie HUREL 26.11.2025

I’ve seen how this plays out in rural clinics. A patient gets prescribed a biologic, then six months later, they stop because the copay jumped again. No one talks about the quiet losses-the missed birthdays, the skipped treatments, the shame. Maybe if we humanized the data, people would care more.

Lauren Zableckis 26.11.2025

Europe got biosimilars faster and didn’t collapse. Their healthcare system isn’t perfect, but they figured out how to balance innovation with access. We’re the outlier here, and it’s embarrassing.

Asha Jijen 26.11.2025

why do we even have 12 years its like monopoly money with needles