It’s a strange truth: if you need a generic pill like lisinopril or metformin, you’ll often pay less at a Walmart pharmacy in Ohio than you would at a corner drugstore in Berlin or Paris. Yet if you need a brand-name drug like Jardiance or Stelara, the price in the U.S. can be three to four times higher than in Europe. How can this happen? Why does the U.S. pay less for generics but way more for branded drugs? The answer isn’t about quality or manufacturing-it’s about how the systems are built.

The U.S. Generic Market Is a High-Volume, Low-Margin Race

In the U.S., 90% of all prescriptions filled are for generic drugs. That’s not because doctors prefer them-it’s because the system pushes them. Pharmacists automatically substitute generics unless the doctor says no. In 49 states, that’s the law. This creates massive pressure on manufacturers to compete on price. Companies like Teva and Mylan sell billions of pills a year, often at razor-thin margins. Sometimes, they sell below cost just to keep their factory running. That’s why you see shortages-when no one can make a profit, they walk away. Then, one company gets a monopoly and hikes prices. But here’s the kicker: even with those occasional spikes, the average price for a 30-day supply of a generic in the U.S. is around $28.50. In Germany, it’s $42.10. In France, it’s even higher. Why? Because European markets don’t have the same volume-driven competition. Only 41% of prescriptions there are for generics. Less competition means less pressure to lower prices.Europe’s System: Government Sets the Price

In Europe, governments don’t wait for drugmakers to set prices. They step in. Countries like Germany, France, and the U.K. use centralized negotiation. They look at what other countries pay. They ask: “Does this drug add real value?” If the answer is no, they won’t pay much-or at all. The U.K.’s NICE agency even turns down drugs that cost too much for the benefit they provide. This isn’t just about fairness. It’s about budget control. European health systems have fixed budgets. They can’t afford to pay whatever a company asks. So they negotiate hard. In the U.S., there’s no single buyer. There are hundreds of private insurers, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), Medicare, Medicaid-all negotiating separately. That sounds like it should drive prices down. But it doesn’t always work that way.Why the U.S. Pays More for Brand-Name Drugs

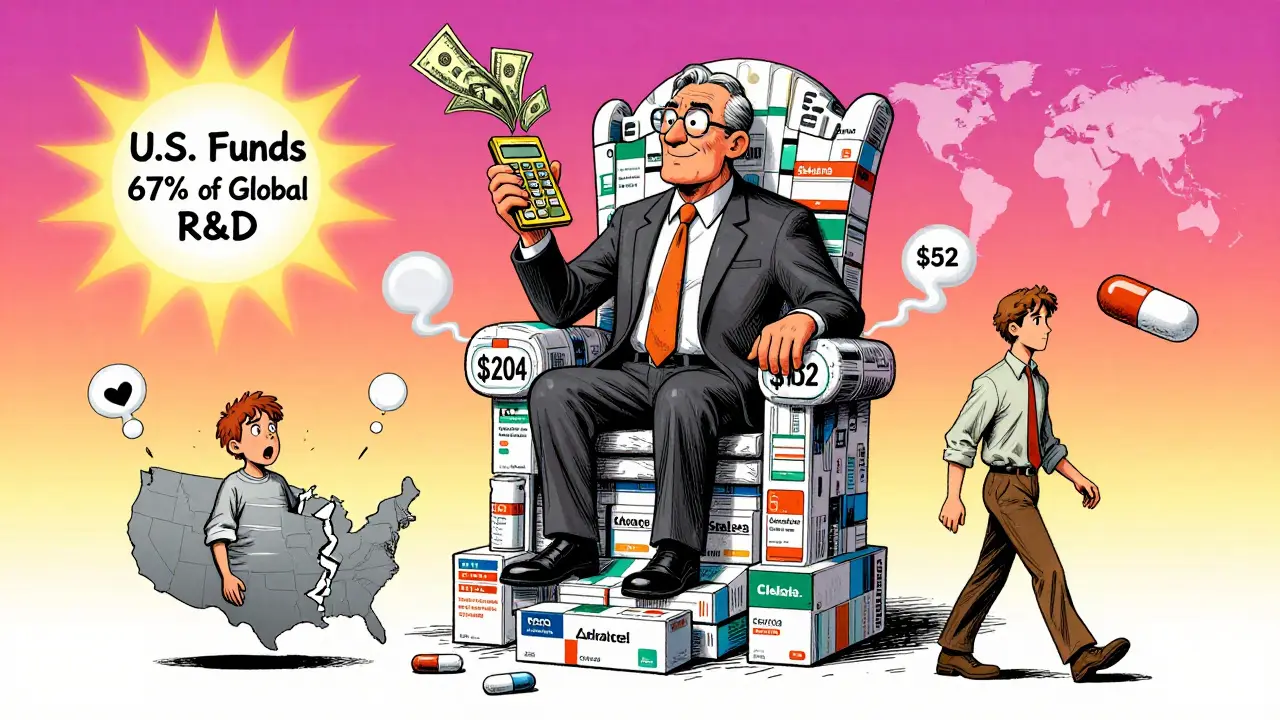

The real imbalance shows up with new drugs. Take Jardiance, a diabetes medication. Medicare negotiated a price of $204 for a month’s supply. In other OECD countries, the average was $52. That’s nearly four times higher. Stelara, used for psoriasis and Crohn’s, costs $4,490 in the U.S. versus $2,822 abroad. Why? Because the U.S. market lets drugmakers charge what they want-until someone pushes back. Drug companies argue they need high prices to fund research. And there’s truth to that. The U.S. accounts for 40% of global drug sales but only 4% of the world’s population. That means American consumers are effectively paying for most of the world’s drug innovation. A 2024 analysis from the Milbank Quarterly found that roughly two-thirds of global pharmaceutical R&D is funded by U.S. prices. When Europe pays less, it’s not because their drugs are cheaper to make-it’s because they’re not paying the full cost of discovery.

The Hidden Rebate System in the U.S.

You might hear that U.S. drug prices are “too high.” But what you see on the shelf isn’t always what’s paid. PBMs-middlemen between insurers and drugmakers-negotiate rebates of 35-40% off list prices for brand-name drugs. Those rebates go straight to insurers or PBMs, not to you. So if your copay is $50 for a drug, the list price might be $200, but the insurer only paid $120 after the rebate. You never see that discount. And if you’re uninsured, you pay the full list price. That’s why people without insurance get shocked by drug bills. In Europe, there are no hidden rebates. Prices are transparent. You know what the government pays. You know what you pay. No middlemen. No secret deals. That’s why European patients often say U.S. pricing feels unfair-they can’t understand why the same pill costs so much more just because of how the system works.What Happens When the U.S. Starts Negotiating Prices?

The Inflation Reduction Act changed things. For the first time, Medicare can directly negotiate prices for a small group of expensive brand-name drugs. The first 10 drugs selected include Jardiance, Stelara, and others. Medicare’s negotiated prices are still higher than in Europe-but they’re down 20-30% from what they were. By 2027, that could mean savings of billions for the government. But here’s the ripple effect: if the U.S. cuts its brand-name prices, drugmakers will need to make up the loss somewhere. Experts like Dana Goldman warn that companies may raise prices in Europe to compensate. That’s what happened when Canada started negotiating lower prices-it led to higher prices in other countries as companies shifted costs around. So while U.S. patients might get relief, it could cost patients elsewhere.

Why Generic Prices Stay Low in the U.S.-And Likely Will

The structure of the U.S. generic market isn’t going away. Pharmacies want generics because they’re profitable. PBMs push them because they get rebates. Patients like them because they’re cheap. Even with new policies, the incentives are aligned to keep generic prices low. Compare that to Europe. Generic manufacturers there don’t have the same volume. They don’t have the same pressure to undercut each other. And they face more regulatory hurdles to enter the market. So even when patents expire, prices don’t crash the way they do in the U.S. A 2025 study in JAMA Health Forum showed that when you account for rebates, the real price difference between U.S. and German generics shrinks-but it doesn’t disappear. The U.S. still wins on price. And it’s not because Americans are smarter. It’s because the system is designed to squeeze every penny out of generic drugs.What This Means for Patients

If you’re in the U.S., you’re getting a deal on generics. A month of generic lisinopril costs $4 at Walmart. In Germany, it’s €15. That’s not a typo. Americans who travel abroad often say they’re stunned by how much more Europeans pay for the same pills. But if you need a new, patented drug, you’re paying more than almost anyone else in the world. And that’s not because your drug is better-it’s because the system lets companies charge more. If you’re on Medicare, you might soon see those prices drop. If you’re uninsured, you’re still on your own. Europeans, meanwhile, get predictable, lower prices on brand-name drugs-but they get fewer new drugs. And when generics do come out, they cost more than they do in the U.S.The Bigger Picture: Who Pays for Innovation?

The real question isn’t who pays less-it’s who pays for the future. The U.S. funds most of the world’s drug research. That’s why new cancer drugs, diabetes treatments, and Alzheimer’s therapies often launch first here. If U.S. prices drop too fast, companies may pull back. Fewer new drugs will come to market. Europe might get cheaper drugs today-but it could pay for it tomorrow with fewer options. The system isn’t broken. It’s just uneven. The U.S. pays more upfront so the world gets new medicines. Europe pays less upfront, so it gets fewer new drugs-but cheaper ones when they’re old. Neither system is perfect. But both work the way they’re built to.Why are generic drugs cheaper in the U.S. than in Europe?

Generic drugs are cheaper in the U.S. because of intense competition and high volume. With 90% of prescriptions filled as generics, manufacturers compete aggressively on price. Pharmacy Benefit Managers and large retailers like Walmart and CVS buy in bulk and demand steep discounts. European markets have lower generic usage (only 41% of prescriptions), less competition, and government-set prices that don’t drop as low. The U.S. system is designed to drive prices down through volume, while Europe prioritizes stability and profit margins.

Do Americans really pay less for all generic drugs?

Mostly, yes-but not always. The average price for a 30-day supply of a generic in the U.S. is about $28.50, compared to $42.10 in Europe. However, some generics have seen shortages because prices dropped so low that manufacturers stopped making them. When that happens, one company may gain a monopoly and raise prices sharply-for example, the price of a generic antibiotic jumped from $20 to $1,800 per pill in one case. So while prices are generally lower, they can spike unpredictably.

Why are brand-name drugs so expensive in the U.S.?

Brand-name drugs are expensive in the U.S. because there’s no central price negotiation. Drugmakers set list prices, and insurers negotiate hidden rebates behind the scenes. Patients without insurance pay full list price. European governments negotiate directly with manufacturers and often refuse to cover drugs they deem too expensive for the benefit they offer. The U.S. system allows higher prices because it funds most of the world’s drug research-companies recoup R&D costs from the U.S. market.

Can the U.S. government lower drug prices without hurting innovation?

It’s possible-but risky. Medicare’s new price negotiation program has already cut prices for some drugs by 25-30%. If expanded, it could reduce U.S. spending significantly. But experts warn that if U.S. prices fall too close to European levels, pharmaceutical companies may raise prices elsewhere to protect profits. That could make new drugs harder to access in Europe and other countries. The goal isn’t to match prices globally-it’s to find a balance where innovation continues without overcharging patients.

Why don’t European countries just copy the U.S. generic model?

They could-but they choose not to. European health systems prioritize predictability and financial control over aggressive price competition. Lower prices mean less profit for manufacturers, which can lead to shortages if companies exit the market. Europe also has stricter rules on generic substitution and requires more clinical data before approving generics. Their system values stability and access over the risk of price volatility. The U.S. model works because of its scale and private market dynamics-but it’s not easily replicated.

Is it true that the U.S. subsidizes drug innovation for the rest of the world?

Yes, according to multiple analyses. The U.S. accounts for about 40% of global pharmaceutical sales but only 4% of the world’s population. Studies show that roughly two-thirds of global drug research funding comes from U.S. revenues. When European countries pay less for brand-name drugs, they benefit from innovations developed with U.S. money. That’s why some experts call it a form of global subsidy-American patients are effectively paying more so others can access the same drugs at lower prices.

blackbelt security 22.01.2026

Walmart’s $4 lisinopril is a miracle. I’ve seen friends in Germany pay €20 for the same thing. No joke - I brought a 90-day supply back from Berlin once and saved my buddy $120. The system’s broken, but at least generics are still a win.

PS: If you’re uninsured and reading this - go to GoodRx. It’s not perfect, but it’s a lifeline.

Patrick Gornik 22.01.2026

Let’s be real - the U.S. isn’t ‘paying less’ for generics. We’re paying in systemic instability. The market doesn’t lower prices - it exterminates competitors until one cartel owns the supply chain. Then boom - $1,800 for a damn antibiotic. That’s not capitalism. That’s predatory feudalism with a pharmacy receipt.

And don’t get me started on PBMs. They’re the vampire squid of healthcare - tentacles everywhere, sucking blood under the guise of ‘negotiation.’ They don’t reduce costs. They just redistribute them into black holes labeled ‘rebates.’

Europe’s system? It’s not ‘broken.’ It’s designed to prevent exactly this kind of chaos. We trade price predictability for price gouging. And we call it freedom.

Also - yes, we fund global R&D. But let’s stop pretending that’s noble. It’s exploitation dressed in lab coats. If you want innovation, pay fair prices. Not ‘whatever the market will bear’ while grandma skips her insulin.

Luke Davidson 22.01.2026

I work in a clinic and I see this every day. A guy came in last week with his wife - both on metformin. He paid $3 at CVS. She paid $48 at her pharmacy because her plan didn’t cover the discount tier. Same pill. Same doctor. Same body. One got treated like a person. The other got treated like a line item.

And yeah - the rebate system is a nightmare. Why do I have to be uninsured to pay $200 for a drug that’s really worth $120? Why can’t that discount go to me?

Also - I’ve had friends from France say they’re jealous of our $4 generics. But they’re also mad we can’t get new drugs fast. It’s not one side being right. It’s two systems trying to solve the same problem with totally different tools.

Maybe we need a hybrid. Not ‘copy Europe’ or ‘fix America.’ But build something that keeps the cheap generics AND stops the brand-name gouging. We’re smart enough to do it. We just need to want it more than we want to profit off each other.

Karen Conlin 22.01.2026

Let me tell you what happens when you’re a single mom on Medicare and your insulin jumps from $35 to $120 overnight - because the PBM renegotiated with the manufacturer and your copay got bumped. You don’t get angry. You get quiet. You start splitting pills. You Google ‘insulin donation programs.’ You cry in the parking lot.

And then you read this post and you realize - it’s not about ‘innovation.’ It’s about who gets to live and who gets to be a footnote in a Bloomberg article.

Yes, the U.S. funds global R&D. But why does that mean WE pay the full tab? Why don’t we all chip in? Why does a country with 4% of the world’s population shoulder 66% of the cost?

It’s not sustainable. It’s not fair. And it’s not moral. We can do better. We just have to choose to.

Also - if you think generics are cheap, try living in a state without automatic substitution laws. Good luck.

asa MNG 22.01.2026

bro why are we even talking about this like its complicated??

drug cos = greedy af

us = pay more so europe can chill

generics = walmart magic

brand names = ripoff

pbms = the real villains (they dont even have a website lmao)

also why do i have to pay 200 for a pill that costs 5 to make??

also also i saw a tweet that said ‘if you’re not mad about this you’re not paying attention’ and i was like… yep. 🤡💊

Sushrita Chakraborty 22.01.2026

As an Indian citizen who has lived in both the U.S. and Europe, I can confirm the disparity is not anecdotal - it is structural. In India, generics are priced below $1, but access remains uneven. In the U.S., the scale of distribution and competitive pressure yields affordability, albeit with volatility. In Europe, the state acts as a gatekeeper - ensuring stability, but often at the cost of delayed access.

What is rarely discussed is the role of intellectual property law. The U.S. grants longer patent extensions and data exclusivity periods, which artificially delay generic entry. Europe, by contrast, permits generic entry immediately after patent expiry - yet prices remain higher due to lower volume and fragmented procurement.

Neither system is ideal. But the U.S. model, while economically efficient, creates moral hazards. The European model, while socially protective, risks innovation stagnation. The solution lies not in imitation, but in hybrid governance - transparent pricing, mandatory rebate pass-through, and global R&D pooling.

Until then, we are all paying - either in money, in health, or in hope.

Heather McCubbin 22.01.2026

Ugh I’m so tired of people acting like this is some deep philosophical debate. It’s not. It’s corporate theft with a PowerPoint presentation.

They don’t care about innovation. They care about stock prices. They don’t care about patients. They care about quarterly earnings.

And now Medicare’s finally trying to fix it? Oh wow. Took them 100 years. Meanwhile, people are choosing between insulin and rent. And you wanna talk about ‘global subsidy’? Nah. It’s a pyramid scheme with white coats.

Also - the fact that you can pay $4 for lisinopril at Walmart but $1,000 for the same pill if you don’t have insurance? That’s not a market. That’s a horror movie.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘rebates.’ Who even gets those? Not me. Not you. Definitely not the person who needs the drug.

Wake up. This isn’t economics. It’s cruelty dressed up as capitalism.

Sawyer Vitela 22.01.2026

90% generic use in the U.S. → high volume → low prices. 41% in Europe → low volume → higher prices. That’s Econ 101.

Brand-name prices? U.S. lacks price controls. Europe has them. End of story.

Rebates? Hidden. Unethical. But irrelevant to patient cost.

Global R&D funding? U.S. pays more → innovation flows here. That’s market logic.

No mystery. No moral crisis. Just systems working as designed.

Shanta Blank 22.01.2026

Okay but imagine this: you’re a CEO of a pharma company. You’ve got a new cancer drug. You can sell it for $500 in Germany. Or $2,000 in the U.S. Which do you pick?

And then you realize - if you pick $500 everywhere, you can’t afford to develop the next one.

So you go all-in on the U.S. market. You make $20 billion. You hire 10,000 scientists. You fund 50 new trials.

Meanwhile, in Berlin, your neighbor is getting the same drug for $50. He’s happy. He thinks you’re a saint.

You? You’re just trying to survive.

So yeah - we’re the suckers. But we’re the suckers who made the cure. And if we stop paying, the cure stops coming.

It’s not fair. But it’s the only system we’ve got.

And honestly? I’d rather pay $200 for a drug that saves my kid than pay $50 for nothing at all.

Tommy Sandri 22.01.2026

Thank you for this comprehensive and well-structured analysis. The distinction between market-driven generic pricing and state-regulated branded drug pricing is critical to understanding the global pharmaceutical landscape. The structural incentives in the United States - volume, substitution mandates, and fragmented payer negotiation - create a unique dynamic that is neither universally equitable nor entirely efficient. European systems, while more predictable, sacrifice responsiveness and innovation velocity. The emerging Medicare negotiation framework represents a necessary, if modest, recalibration. However, the long-term sustainability of global R&D funding requires multilateral dialogue, not unilateral cost-shifting. The challenge is not to choose between affordability and innovation, but to design a system that harmonizes both - through transparency, coordinated pricing, and equitable risk-sharing. The status quo is untenable. The path forward demands both moral clarity and economic pragmatism.