When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA know it will? The answer lies in bioavailability studies - the invisible science that makes generic drugs safe, effective, and affordable.

What Bioavailability Really Means

Bioavailability isn’t just about whether a drug gets into your body. It’s about how fast and how much of it gets there. The FDA defines it precisely: the rate and extent to which the active ingredient is absorbed into your bloodstream and reaches the site where it needs to work. Think of it like pouring water into a cup. If you dump it all at once, the cup fills quickly - that’s high rate of absorption. If you only fill it halfway, even slowly, you get less total water - that’s low extent. For a drug, those two factors are measured as Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure over time). These aren’t theoretical numbers. They’re measured in real people. Volunteers take the drug, and blood samples are drawn every 15 to 60 minutes for up to 72 hours. Labs then use highly accurate methods to detect how much of the drug is in each sample. The results are plotted into a curve - the concentration-time profile. From that curve, scientists calculate AUC and Cmax.Why Bioequivalence Is the Gold Standard

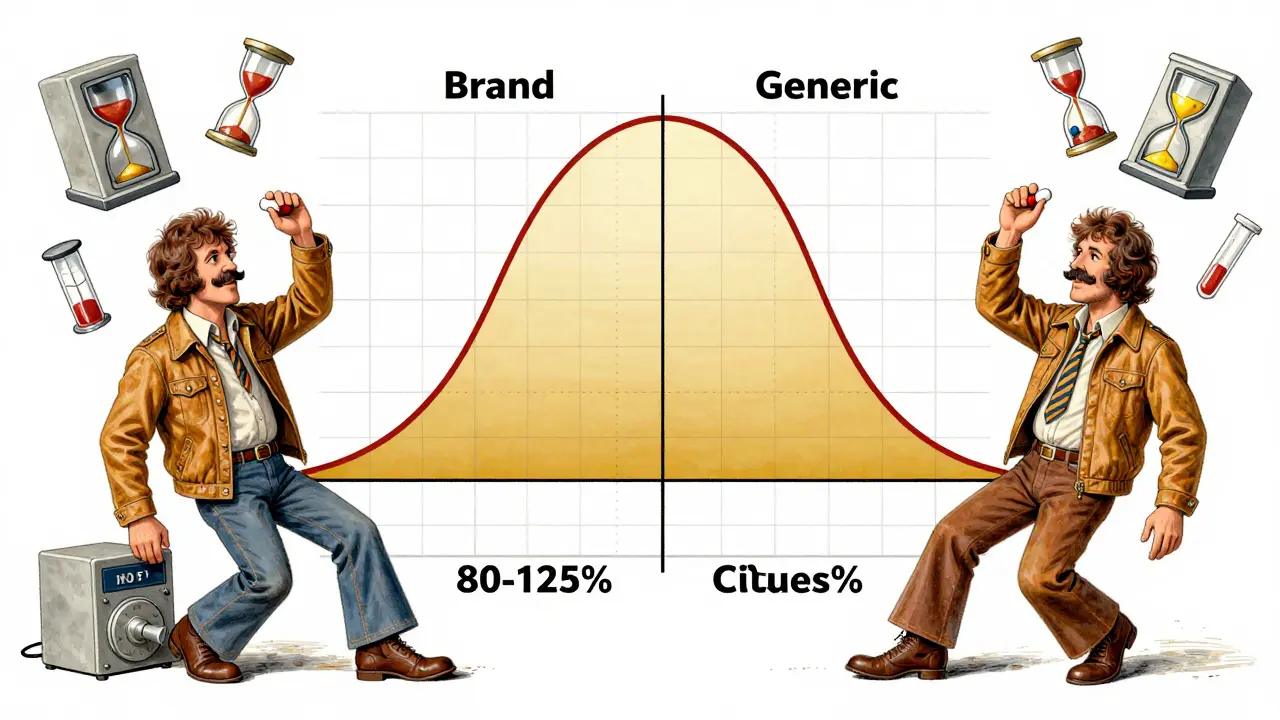

Generic manufacturers don’t have to repeat the expensive clinical trials that brand-name companies ran. Instead, they prove bioequivalence - meaning their version behaves almost identically to the original in the body. The rule is simple: the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand-name drug’s AUC and Cmax must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand-name drug gives you an AUC of 100 units, the generic must deliver between 80 and 125 units. The average ratio should be close to 100% - usually within 95-105%. This isn’t a random number. It’s based on decades of clinical data. A 20% difference in absorption rarely affects how a drug works for most conditions. For example, if a blood pressure pill’s absorption drops by 15%, it’s unlikely to cause your blood pressure to spike dangerously. That’s why regulators accept this range. But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine - even small changes can matter. For these, the acceptable range tightens to 90-111%. The FDA requires extra scrutiny for these drugs because the line between effective and toxic is thin.How the Studies Are Done

Most bioequivalence studies follow a crossover design. Healthy volunteers take the brand-name drug in one period, then the generic in another - with a washout period in between to clear the first drug from their system. Half the group gets the brand first; the other half gets the generic first. This design cancels out individual differences in metabolism. Typically, 24 to 36 people participate. The sample size isn’t chosen randomly - it’s calculated to give the study at least 80% power to detect a meaningful difference. Too few people, and you might miss a real problem. Too many, and you waste resources. The bioanalytical methods used to measure drug levels in blood must be validated to exact standards. Accuracy must be within 85-115% of the true value. Precision (repeatability) must have a coefficient of variation under 15%. Labs don’t guess - they use mass spectrometry and other high-tech tools to get exact numbers.

When Bioequivalence Isn’t Enough

For simple pills - immediate-release, oral, water-soluble drugs - bioequivalence works brilliantly. But not all drugs are that simple. Extended-release tablets, inhalers, gels, and injectables behave differently. A generic extended-release capsule might release its drug over 12 hours, but if it releases too fast at first or too slow later, it won’t work the same. For these, the FDA requires multiple time-point comparisons - not just AUC and Cmax, but also specific concentrations at 4, 8, and 12 hours. Some drugs can’t be measured in blood at all. Topical creams, for example, might act locally on the skin. In those cases, researchers use pharmacodynamic endpoints - like measuring skin redness or vasoconstriction - to prove equivalence. And then there are highly variable drugs. Some people metabolize them quickly; others slowly. For these, the FDA allows a special method called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). If the brand-name drug shows high variability in the study (within-subject CV over 30%), the acceptance range widens to 75-133%. This prevents good generics from failing just because the original drug itself behaves inconsistently.What About Patient Stories?

You’ve probably heard stories: “I switched to generic and felt awful.” “My seizures came back.” “My cholesterol spiked.” These cases are real - but rare. Between 2020 and 2023, the Epilepsy Foundation collected 187 reports of increased seizures after switching to generic levetiracetam. But after investigation, the FDA found only 12 cases (6.4%) were possibly linked to bioequivalence issues. The rest were due to missed doses, stress, or other factors. Cardiologist Dr. Michael Chen saw three patients out of 3,000 who had palpitations after switching from brand-name to generic amlodipine. All improved when switched back. That’s 0.1%. For every one of those cases, there are thousands of patients who take generics without issue. The Generic Pharmaceutical Association estimates 90% of Americans can’t tell the difference between brand and generic in terms of effectiveness. That’s not luck - it’s science.

Why This System Works

Since the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, the FDA has approved over 15,000 generic drugs. Today, 97% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics - and they cost just 26% of what brand names do. The system isn’t perfect. Complex generics - like inhalers or long-acting injectables - are harder to test. In 2022, 22% of generic applications involved these complex products, up from 8% in 2015. That’s why the FDA is investing in new tools: AI models that predict bioavailability from formulation data, and IVIVC (in vitro-in vivo correlation) models that link lab tests to real-world performance. In 2023, the FDA’s collaboration with MIT showed machine learning could predict AUC ratios with 87% accuracy across 150 drug compounds. That could eventually cut the number of human studies needed. But for now, blood samples, pharmacokinetic curves, and the 80-125% rule remain the backbone of generic approval. And for good reason: they’ve kept millions of people healthy while saving the U.S. healthcare system hundreds of billions of dollars.What You Should Know

If you’re prescribed a generic, you can trust it. The FDA doesn’t approve generics that are “close enough.” They require proof they’re nearly identical in how your body handles them. If you notice a change after switching - whether it’s side effects, lack of effectiveness, or new symptoms - talk to your doctor. Don’t assume it’s the drug. But also don’t dismiss it. For some, especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs, even small differences matter. For most people, though, generics work just as well. And that’s not because of luck or marketing. It’s because of rigorous science - measured in blood, calculated in curves, and enforced by standards that have held up for 40 years.Are bioavailability studies required for all generic drugs?

Yes, for most oral solid dosage forms like tablets and capsules, bioavailability and bioequivalence studies are required. But there are exceptions. Drugs classified under BCS Class 1 (high solubility, high permeability) may qualify for a waiver if their formulation matches the brand-name product exactly. In vitro tests can sometimes replace human studies for these simple drugs. For non-oral drugs like creams or inhalers, different methods - like pharmacodynamic testing - are used instead.

Why is the bioequivalence range 80-125%? Isn’t that too wide?

No, it’s not too wide - it’s scientifically justified. Studies show that a 20% difference in absorption rarely affects clinical outcomes for most drugs. The 90% confidence interval ensures the true difference is unlikely to exceed 25% in either direction. For example, if a generic delivers 85% of the brand’s exposure, it’s still within safe limits. The range was chosen based on decades of real-world data, not guesswork. Narrower ranges are used only for high-risk drugs like warfarin or digoxin.

Can a generic drug fail bioequivalence testing?

Yes. If the 90% confidence interval for AUC or Cmax falls outside 80-125%, the drug fails. For example, if the upper bound of the AUC ratio hits 1.30 (130%), even if the average is 1.16, the product is rejected. This happens occasionally - often because of formulation issues like wrong excipients, poor dissolution, or inconsistent manufacturing. Failed studies are not made public, but companies must resubmit with improved formulations.

Do bioequivalence studies use patients or healthy volunteers?

Most studies use healthy volunteers - usually 24 to 36 people - because they provide consistent, predictable responses. Using patients with the disease could introduce too many variables, like liver or kidney dysfunction, that skew results. Once a generic is approved, post-marketing studies may involve patients to monitor real-world performance. But the initial proof of equivalence relies on healthy subjects for accuracy and control.

Why do some generics cost less than others if they’re all bioequivalent?

Price differences come from manufacturing scale, competition, and supply chain efficiency - not quality or effectiveness. Two bioequivalent versions of the same drug can cost differently because one company produces it in higher volumes, has lower overhead, or negotiated better raw material deals. The FDA doesn’t regulate price - only safety and equivalence. So a cheaper generic isn’t inferior; it’s just more efficiently made.

Ashok Sakra 19.01.2026

This is why I hate generics, man. I took one for my anxiety and I felt like I was turning into a zombie. Like, my brain just shut off. Brand name? I felt human. Now I pay extra just to not feel like a robot.

Kelly McRainey Moore 19.01.2026

Honestly? I switched to generic lisinopril last year and haven’t had a single issue. My BP’s stable, no dizziness, no weird side effects. Sometimes the hype is just hype.

michelle Brownsea 19.01.2026

It's fascinating-yet profoundly concerning-that we've reduced human physiology to a 90% confidence interval between 80% and 125%. What if your body doesn't fall within the statistical norm? What if you're the 1 in 10,000 who metabolizes differently? The system isn't designed for you-it's designed for averages. And that's terrifying.

Sangeeta Isaac 19.01.2026

Bro, I once took a generic Adderall and thought I turned into a ghost. Like, I could feel my soul leaving my body. Then I switched back and boom-focus returned. Not saying it's the drug, but... why risk it? I'm not a lab rat.

Stephen Rock 19.01.2026

80-125%? That’s not science. That’s corporate math wrapped in a lab coat. Real people aren’t averages. The FDA’s playing roulette with lives and calling it ‘efficiency.’

Andrew Rinaldi 19.01.2026

I appreciate the depth here. The fact that they adjust ranges for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs shows the system isn’t blind-it’s adaptive. It’s not perfect, but it’s thoughtful. And that’s more than most regulatory bodies manage.

Philip Williams 19.01.2026

The use of crossover designs with washout periods is methodologically sound. Eliminating inter-individual variability through within-subject comparison is the gold standard in pharmacokinetics. This isn’t just bureaucracy-it’s rigorous science.

Barbara Mahone 19.01.2026

My grandmother takes generic levothyroxine. She’s 82, lives in Florida, and her TSH levels are perfect. She doesn’t know what AUC means. She just knows she feels fine. Sometimes the simplest stories are the most powerful.

MAHENDRA MEGHWAL 19.01.2026

Respected colleagues, I must express my profound admiration for the regulatory framework established under the Hatch-Waxman Act. The precision with which bioequivalence is assessed reflects the highest standards of public health stewardship. May this model be emulated globally.

Dee Monroe 19.01.2026

You know, I used to think generics were just cheaper versions, but now I see it’s like this beautiful dance between chemistry, statistics, and human biology-every curve, every blood draw, every 15-minute interval is a tiny act of trust. Trust that science, not profit, is guiding this. And honestly? That’s kind of beautiful.

Alex Carletti Gouvea 19.01.2026

Why do we let foreign labs test our drugs? We used to make this stuff here. Now we’re trusting some factory in India to get the math right so we can save five bucks on a pill. That’s not progress. That’s surrender.