By 2025, more than 1 in 5 commonly prescribed medications in the U.S. and Europe will face recurring shortages. This isn’t just a temporary hiccup-it’s a pattern getting worse. Hospitals are rationing insulin. Cancer patients wait weeks for chemo drugs. Pediatric antibiotics disappear from shelves for months. And no one’s talking about why-or how to stop it.

Why Drug Shortages Are Getting Worse

Drug shortages used to be rare. Now they’re predictable. The main reason? A broken supply chain built on thin margins and single-source manufacturing. Over 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for common drugs come from just two countries: India and China. If a factory in Gujarat shuts down for a regulatory inspection, or a port in Shanghai gets blocked by weather, the ripple effect hits pharmacies in Sydney, Toronto, and Berlin within weeks.

It’s not just about production. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported over 1,200 drug shortage notices between 2020 and 2025. Roughly 60% of those were linked to manufacturing quality issues-contamination, equipment failure, or failure to meet cleanliness standards. These aren’t random accidents. They’re symptoms of underinvestment. Many generic drug makers operate on profit margins under 5%. When a factory needs a $2 million upgrade to meet new hygiene rules, companies often delay it… until they get shut down.

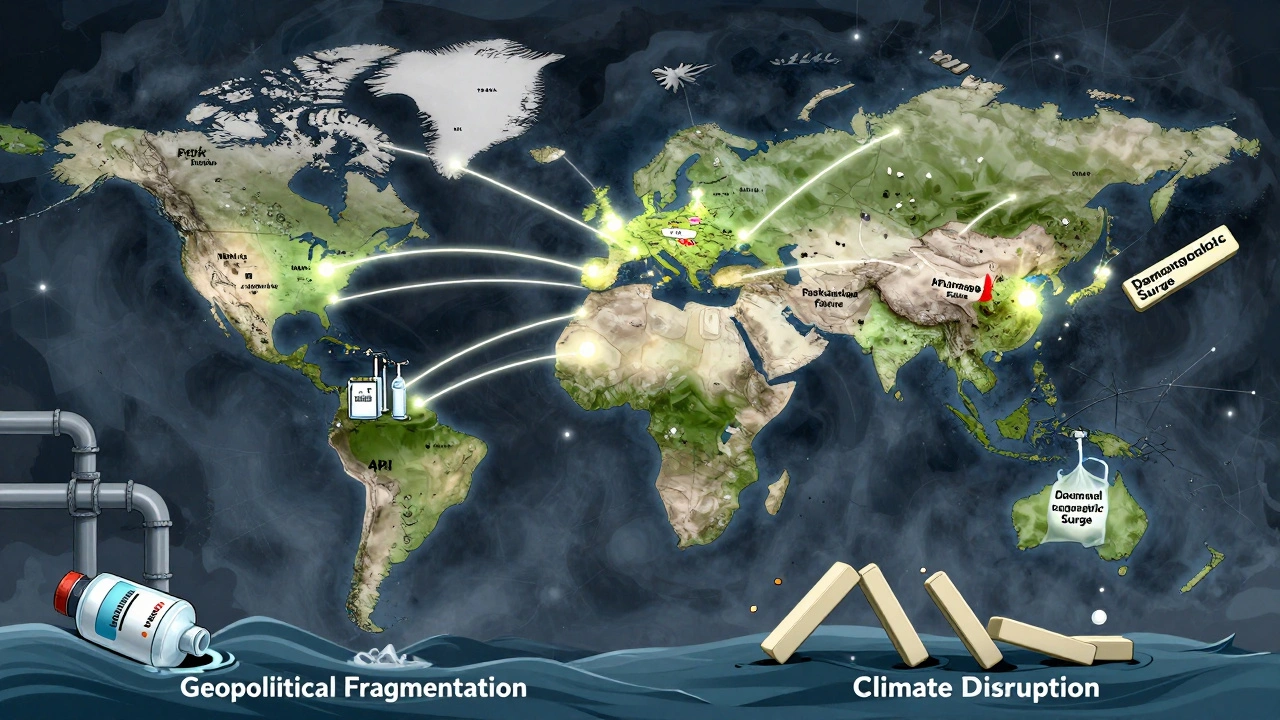

The Three Big Drivers of Future Scarcity

Three forces are pushing drug scarcity into a new era:

- Geopolitical fragmentation-Countries are pulling supply chains home. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act pushed domestic API production, but it takes 3-5 years to build a new plant. Meanwhile, India has restricted exports of 24 critical APIs since 2023 to protect its own market.

- Climate disruption-Extreme heat and floods damage raw crop sources. Vanillin, a key flavoring in some liquid medications, comes from vanilla beans grown in Madagascar. Droughts there cut supply by 40% in 2024. Similar disruptions are hitting quinine (for malaria), digitalis (for heart failure), and even penicillin precursors.

- Demographic pressure-By 2030, 20% of the global population will be over 65. Older adults take 5-7 medications on average. Demand for blood thinners, diabetes drugs, and heart medications is rising faster than supply. The World Bank estimates global pharmaceutical demand will grow 38% by 2030, but manufacturing capacity is only projected to rise 12%.

Combine these, and you get a perfect storm. A single shortage in one region can trigger panic buying, stockpiling, and black-market pricing. In 2024, a shortage of metformin-used by over 120 million people-sparked a 200% price spike on online marketplaces in Latin America and Eastern Europe.

How Forecasting Works-And Why It’s Still Falling Short

Forecasting drug shortages isn’t like predicting the weather. It’s more like trying to guess which domino will fall next in a 10,000-piece chain.

Most health agencies use basic models: track production volumes, inventory levels, and past shortage patterns. But these miss the hidden links. For example, if a supplier in Portugal stops making a packaging component for a blood pressure drug, the drug itself doesn’t disappear overnight. But once the last batch of bottles is used, the drug vanishes-because no one tracks that packaging component’s supply chain.

The best forecasting tools now combine:

- Real-time shipment data from global ports

- Regulatory inspection records from the FDA, EMA, and WHO

- Supplier financial health scores (bankruptcy risk, debt levels)

- Climate risk maps for crop-based ingredients

- Political instability indexes in manufacturing hubs

Companies like IQVIA and Datavant have built AI models that scan 200+ data streams. Their models flagged the 2025 metformin shortage six months before it hit shelves. But only 12% of hospitals use these tools. Most still rely on supplier calls and email alerts.

Who Gets Hit Hardest-and Why

Not all drug shortages affect everyone equally.

Generic drugs are the most vulnerable. They’re cheap, so companies make them in low-cost countries with weak oversight. If a generic version of amoxicillin or levothyroxine runs out, there’s no brand-name backup. Patients can’t just pay more-they can’t get it at all.

Specialty drugs for rare diseases are next. These are made in tiny batches. One production error can wipe out a year’s supply. In 2024, a single contamination in a U.K. lab caused a 9-month global shortage of a drug used by fewer than 3,000 people. Many died waiting.

And then there’s the hidden group: children. Pediatric formulations often use different excipients or dosing formats. If a manufacturer stops making the liquid version of a drug because it’s not profitable, there’s no easy workaround. Parents have to crush pills or mix powders themselves-risking overdose or underdose.

What’s Being Done-And What’s Not

Some governments are trying. The U.S. passed the Drug Supply Chain Security Act in 2013. It’s supposed to track drugs from factory to pharmacy. But it doesn’t require real-time data. Most companies still use paper logs or outdated barcodes.

India banned exports of 24 APIs in 2023. That helped its own citizens-but made shortages worse elsewhere. The European Union is pushing for regional API production. France and Germany are funding new plants. But it takes 4 years to get regulatory approval. By then, the shortage may already be here.

The biggest gap? No one tracks inventory at the pharmacy level. Hospitals know when they’re low. But corner pharmacies? They don’t report. A drug can vanish from 500 pharmacies before anyone notices.

What You Can Do-Even If You’re Not a Pharmacist

You don’t need to be in government or pharma to help. Here’s what works:

- Ask your pharmacist-If your medication is out, ask if there’s an alternative. Many doctors don’t know about interchangeable generics. Pharmacists do.

- Don’t stockpile-Buying extra doses hoards supply and makes shortages worse. One person hoarding 6 months of metformin can leave 10 others without.

- Report shortages-If your pharmacy runs out, tell them. Then call your state health department. The more reports they get, the faster they act.

- Support policy change-Push for laws that require real-time reporting of inventory levels. Demand that governments fund backup production for critical drugs.

There’s no magic fix. But if we treat drug shortages like a system failure-not a series of accidents-we can start fixing them.

What’s Next: The 2026-2030 Outlook

By 2027, experts predict at least 40 common drugs will be in permanent shortage unless supply chains are rebuilt. The biggest risks:

- Insulin-Demand will rise 50% by 2030. Production can’t keep up.

- Levothyroxine-Used by 20 million Americans. One factory makes 70% of the global supply.

- Vancomycin-Last-resort antibiotic. Only 3 manufacturers make it. One shutdown = crisis.

- IV saline-Used in 90% of hospital admissions. Most bags are made in China. A single typhoon can cut supply for months.

The good news? The tools to predict and prevent these shortages exist. What’s missing is the will to use them.

By 2030, we could have a world where every critical drug is backed by at least two reliable suppliers. Where climate risks are built into procurement contracts. Where children’s medicines aren’t an afterthought.

Or we could keep waiting for the next shortage to hit-and react again.

Why are generic drugs more likely to have shortages than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs have razor-thin profit margins-often under 5%. Manufacturers cut corners to stay profitable: using single suppliers, delaying equipment upgrades, and skipping safety checks. Brand-name drugs have higher prices and more competition among makers, so they invest in backup production and better quality control. When a factory fails, generics have no fallback.

Can we just make more drugs in the U.S. or Europe to avoid shortages?

It’s possible-but slow and expensive. Building a new API plant takes 4-7 years and costs $200 million to $500 million. Regulatory approval adds another 2 years. By the time a new plant opens, the shortage may have passed-or a new one has started. The goal isn’t just more production. It’s smarter, distributed production with redundancy built in.

Are drug shortages getting worse because of inflation?

Inflation doesn’t cause shortages, but it makes them worse. When costs for energy, labor, and shipping rise, drug makers cut production of low-margin drugs first. They focus on high-profit items. So, the cheapest, most essential drugs-like antibiotics and insulin-are the first to disappear. Inflation pushes companies to make choices that hurt patients.

How do climate change and weather affect medicine supply?

Many drugs start as plants. Vanillin (for flavoring), quinine (for malaria), and digitalis (for heart failure) come from crops grown in vulnerable regions. Droughts in Madagascar, floods in India, and heatwaves in Brazil have already cut yields. Even packaging materials like paper and plastic rely on agriculture and oil-both climate-sensitive. A single extreme weather event can break a chain that spans continents.

What’s the biggest blind spot in current shortage forecasting?

The packaging. Most systems track the drug itself-not the bottle, the cap, the label, or the syringe. But if one of those fails, the drug can’t be delivered. A factory in Poland might make the medicine perfectly, but if the glass vials come from a single supplier in Turkey and they’re delayed, the drug sits unused. No one’s tracking that.

Is there a global database that tracks drug shortages in real time?

No. The FDA and EMA have lists, but they’re updated weekly or monthly-and only include drugs they’ve officially flagged. Many shortages go unreported until pharmacies call in. There’s no real-time, global, public system that pulls data from manufacturers, distributors, and pharmacies all at once. That’s the missing piece.

Levi Cooper 11.12.2025

Let’s be real-this whole mess is because we let India and China run the show. We used to make our own drugs. We had the factories, the workers, the tech. Now we’re begging for pills like we’re in a third-world country. It’s not a shortage-it’s a national security failure. We need to ban imports from these places until they play fair. Period.

Laura Weemering 11.12.2025

It’s not just supply chains… it’s ontological collapse. The pharmaceutical-industrial complex has externalized all its existential risks onto the vulnerable-patients, children, the elderly. We’ve commodified life-saving molecules to the point where they’re no longer *rights*, but *commodities* with fluctuating liquidity… and now, the market has defaulted. We’re living in the aftermath of a bioethical recession.

Reshma Sinha 11.12.2025

As someone from India, I see this daily-our factories are working overtime, but we’re being blamed for the global fallout. We’re not the problem; the *system* is. We need multi-country alliances-not blame games. Let’s co-invest in regional API hubs across Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. India can lead if we get fair partnerships, not sanctions.

nikki yamashita 11.12.2025

My grandma couldn’t get her thyroid meds last month. Took her 3 weeks. She cried. We all did. This isn’t policy-it’s people. Let’s fix it before more folks get hurt.

Rob Purvis 11.12.2025

Wait-so you’re saying the biggest blind spot is *packaging*? Like, the bottle? The cap? The label? That’s wild. I work in logistics, and I’ve seen this: a shipment of 10 million insulin vials sits idle because the rubber stoppers from Slovakia got delayed. No one tracks stoppers. No one even thinks to. We’re treating drugs like magic beans, not engineered systems.

Stacy Foster 11.12.2025

This is all a CIA op. They let the shortages happen so they can push mandatory vaccines and digital IDs under the guise of 'public health.' You think they don’t control the API supply? They own the factories. They own the patents. They own the pharmacies. The metformin spike? A controlled burn to make you beg for their 'solution.' Wake up.

Lawrence Armstrong 11.12.2025

Biggest thing people miss: most shortages aren’t from lack of drug-they’re from lack of *labels*. I worked at a pharma co. Once, we had 2 million doses ready to ship… but the FDA rejected the label font size. Took 4 months to fix. No one talks about that. 😔

Audrey Crothers 11.12.2025

My cousin’s kid needs a rare chemo drug. They’ve been out for 8 months. The hospital says, 'We’re waiting.' But no one’s *doing* anything. We need a hotline. A map. A real-time tracker. Like Uber for life-saving meds. Please, someone build this. 🙏

sandeep sanigarapu 11.12.2025

India exports 40% of global generic drugs. We are not the cause-we are the backbone. Blaming us will not solve the problem. Instead, let us collaborate with the U.S. and EU to establish multi-national regulatory standards. This is not a crisis of supply. It is a crisis of coordination.