Opioid Dose Adjustment Calculator

Dosing Guidance for Liver Disease

When liver function is impaired, opioids accumulate in your body. This tool helps estimate adjusted doses based on liver disease severity. Always consult your doctor before changing any medication.

Recommended Starting Dose

of standard dose

For Morphine, the adjusted dose is based on:

- Half-life extension from 2-3 hours to >12 hours

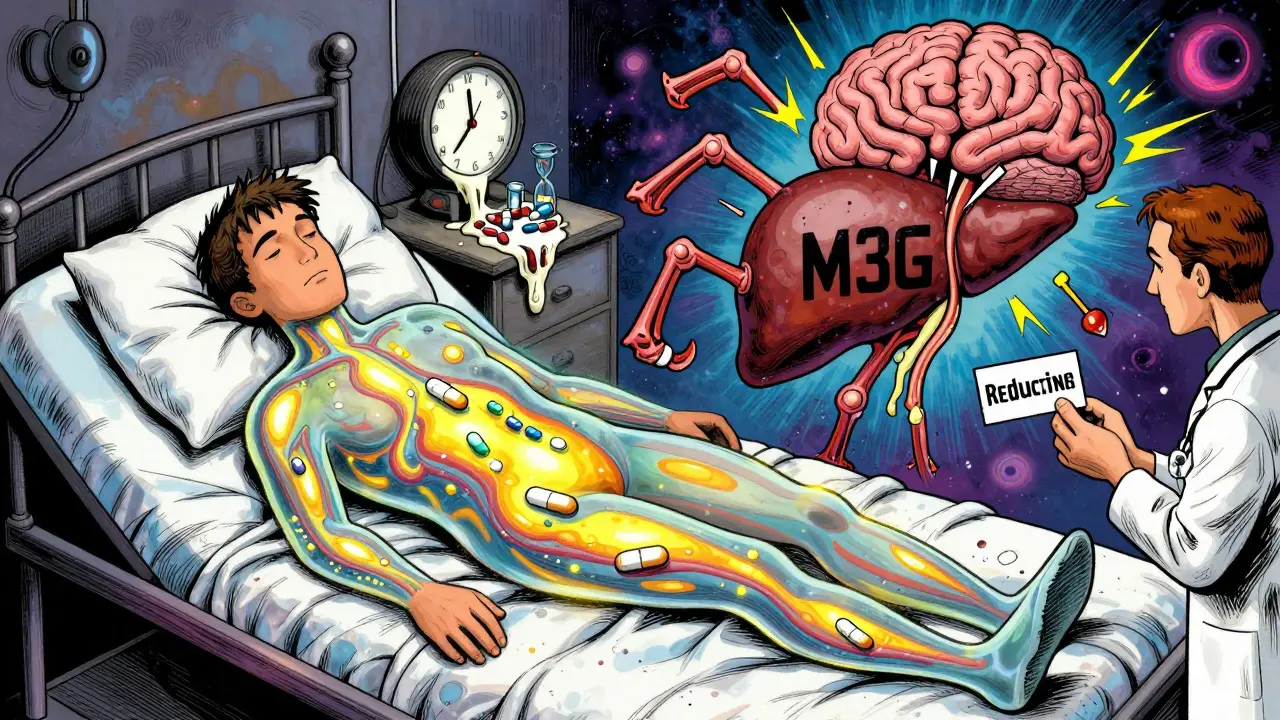

- Accumulation of toxic metabolite M3G

Start with 50% of normal dose

Key Safety Information

Morphine

High risk: Metabolite M3G accumulates, causing seizures or agitation. Reduce dose by 50-75% in severe liver disease.

Oxycodone

Reduced dose needed: 30-50% of normal dose in severe liver disease. Avoid extended-release forms.

Fentanyl Patches

Bypasses liver metabolism. Use 90-100% of standard dose but monitor for delayed effects.

Buprenorphine

Preferred option: Ceiling effect on respiratory depression makes it safer.

When your liver is damaged, taking opioids isn’t just riskier-it can be dangerous in ways most people don’t expect. Pain relief shouldn’t come with a hidden cost, yet for people with liver disease, common painkillers like morphine or oxycodone can build up in the body and cause serious harm. This isn’t about taking too much. It’s about how your body processes these drugs when the liver can’t keep up.

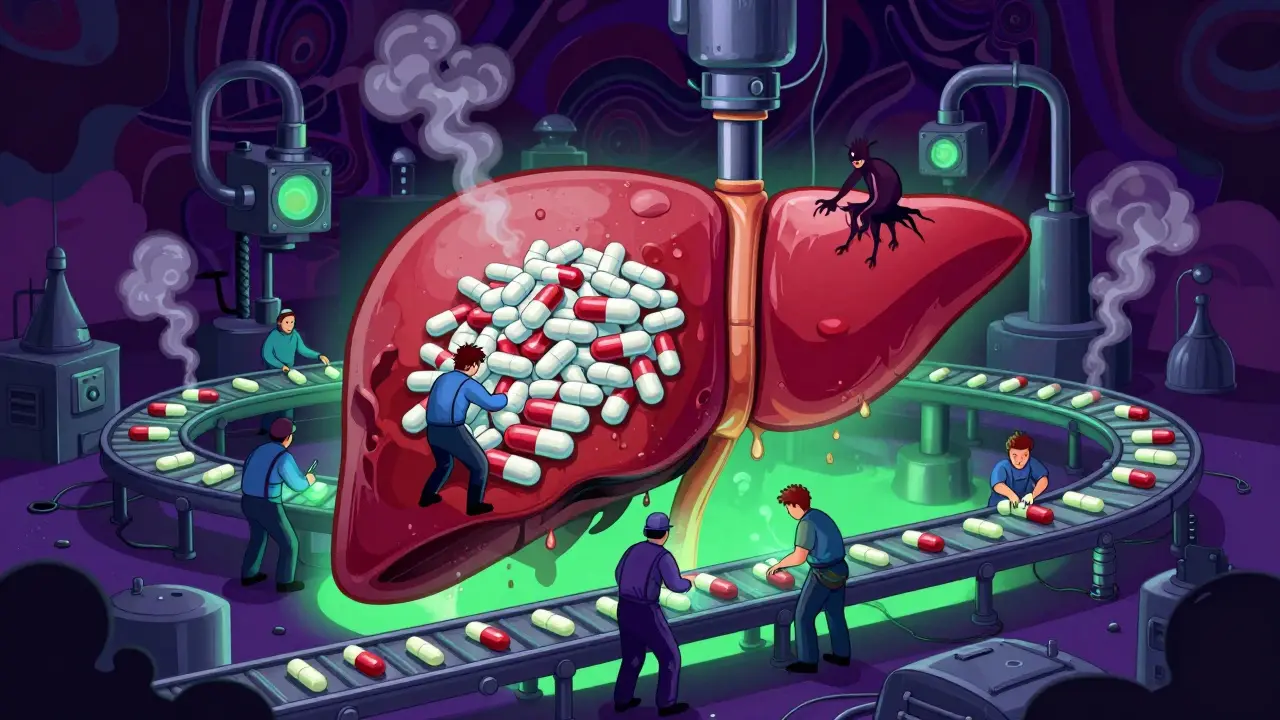

How the Liver Normally Breaks Down Opioids

Your liver is the main factory for processing opioids. It uses two major systems: cytochrome P450 enzymes and glucuronidation. These systems turn opioids into compounds your body can flush out through urine or bile. For example, morphine gets changed into morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G), which still helps with pain, and morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G), which doesn’t help pain but can cause seizures or confusion. Oxycodone is broken down by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 enzymes into active and inactive forms. When the liver works normally, these processes happen quickly and safely.

But when liver disease is present-whether from alcohol, fatty liver, or hepatitis-these systems slow down. The enzymes don’t work as well. That means opioids stick around longer. Instead of being cleared in a few hours, they can hang around for days. This isn’t a minor delay. It’s a major shift in how the drug behaves in your body.

What Happens When the Liver Can’t Keep Up

In advanced liver disease, opioid clearance drops by 50% or more. For morphine, the half-life-the time it takes for half the drug to leave your system-can jump from 2-3 hours to over 12 hours. For oxycodone, it can stretch from the normal 3.5 hours to an average of 14 hours, and in severe cases, up to 24 hours. That means if you take a dose every 6 hours, you’re essentially stacking doses on top of each other without giving your body time to clear the last one.

Studies show that in people with severe liver impairment, the maximum concentration of oxycodone in the blood increases by 40%. That’s not a small change. It’s enough to push someone from therapeutic levels into toxic territory. Symptoms like extreme drowsiness, slow breathing, confusion, or even coma become much more likely. These aren’t rare side effects-they’re predictable outcomes of altered metabolism.

Morphine is especially risky because its metabolites aren’t just inactive-they’re harmful. M3G builds up in liver failure and can cause neurological side effects even when the original drug level seems low. That’s why someone might feel fine after a dose but still develop seizures or agitation hours later. The problem isn’t the morphine itself-it’s what the liver turns it into.

Different Liver Diseases, Different Risks

Not all liver damage affects opioid metabolism the same way. In alcohol-related liver disease, the CYP2E1 enzyme becomes overactive. That might sound good, but it actually creates toxic byproducts that stress the liver even more. At the same time, CYP3A4-the enzyme that breaks down oxycodone and fentanyl-becomes less active. So you get one system speeding up dangerously while another slows down.

In non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is now the most common liver condition worldwide, CYP3A4 activity drops by up to 30%. That means even if you don’t drink alcohol, if you have fat in your liver, your body may process opioids slower. The same is true for people with type 2 diabetes, which often goes hand-in-hand with NAFLD. These conditions are so common that many people taking opioids for chronic pain may be at higher risk without even knowing it.

Chronic opioid use also harms the gut microbiome, which sends inflammatory signals straight to the liver. This creates a feedback loop: opioids → gut imbalance → liver inflammation → worse metabolism → more opioid buildup → more inflammation. It’s a cycle that’s hard to break once it starts.

Dosing Changes You Need to Know

Doctors can’t treat liver disease and pain the same way they treat healthy patients. Guidelines are clear: start low, go slow, and monitor closely.

- Morphine: In early liver disease, reduce the starting dose by 25-50%. In advanced failure, cut the dose and extend the time between doses-maybe from every 4 hours to every 8-12 hours.

- Oxycodone: For severe liver impairment, start with only 30-50% of the normal dose. Never use extended-release forms. Monitor for sedation and breathing changes daily.

- Methadone: This one’s tricky. It’s broken down by several enzymes, so it’s less dependent on one pathway. But there are no solid dosing rules for liver disease. Use with extreme caution and only under specialist supervision.

- Fentanyl and buprenorphine: These are often better choices because they can be given as patches or films that bypass the liver’s first-pass metabolism. Transdermal fentanyl avoids the gut and liver entirely, making it safer for people with cirrhosis. Buprenorphine has a ceiling effect on respiratory depression, which lowers overdose risk.

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule. But the pattern is consistent: if your liver isn’t working right, your opioid dose needs to be lower than what’s listed on the bottle.

Why Some Opioids Are Safer Than Others

Not all opioids are created equal when it comes to liver disease. Morphine and codeine are high-risk because they rely heavily on liver enzymes and produce toxic metabolites. Oxycodone and hydrocodone are risky too, especially in advanced disease.

Buprenorphine stands out because it’s metabolized by multiple pathways and has a built-in safety limit-after a certain dose, it stops increasing its effect on breathing. That’s why it’s often used in addiction treatment and is considered safer for people with liver damage.

Fentanyl patches are another option. Since they deliver the drug through the skin, they avoid the liver’s first pass. That means less strain on a weakened liver. But they take hours to start working and can’t be adjusted quickly if pain changes. That’s why they’re better for steady, long-term pain-not sudden flare-ups.

Hydromorphone and tramadol are less studied in liver disease, but tramadol’s metabolism depends on CYP2D6, which can vary wildly between people. That unpredictability makes it risky in anyone with liver problems.

What to Watch For: Signs of Opioid Toxicity

When opioids build up in liver disease, symptoms don’t always look like a typical overdose. You might not see pinpoint pupils or slow breathing right away. Instead, watch for:

- Unusual drowsiness or confusion that doesn’t go away

- Slurred speech or trouble staying awake

- Nausea or vomiting that’s worse than usual

- Agitation, hallucinations, or seizures (especially with morphine)

- Slowed breathing, even if it’s mild

- Low blood pressure or dizziness when standing

If you’re on opioids and have liver disease, these signs mean stop the drug and call your doctor-don’t wait. Toxicity can develop quietly, especially in older adults or those with multiple health issues.

What’s Still Unknown

There are big gaps in what we know. We don’t have clear dosing guidelines for most opioids in liver disease. Fentanyl’s metabolism in cirrhosis isn’t well studied. The same goes for tapentadol, naloxone, and other newer agents. Most research is based on small studies or case reports. We need large, real-world trials to confirm safe doses across different types of liver disease-alcoholic, viral, fatty, autoimmune.

Another unanswered question: do opioids make liver damage worse over time? Some animal studies suggest yes, through inflammation and gut damage. But human data is limited. We don’t yet know if switching from morphine to buprenorphine slows liver decline. That’s a critical question for long-term pain patients.

Until then, the safest approach is to use the lowest effective dose, choose the safest opioid for your liver condition, and avoid combinations. Never take extra doses if pain returns. Don’t mix opioids with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or sleep aids. Those combinations are deadly when the liver is already struggling.

What You Can Do

If you have liver disease and need pain relief:

- Ask your doctor to check your liver function before starting any opioid.

- Request a low starting dose-even if your pain is severe.

- Ask which opioid is safest for your type of liver disease.

- Use transdermal options like fentanyl patches if appropriate.

- Track your symptoms daily: sleepiness, confusion, breathing changes.

- Never adjust your dose on your own.

- Consider non-opioid options like acetaminophen (in low doses), gabapentin, or physical therapy.

There’s no perfect solution. But with the right knowledge and caution, you can manage pain without putting your liver at greater risk.

Katelyn Slack 5.01.2026

i had no idea liver issues could mess with pain meds like this. my aunt’s on oxycodone and has fatty liver-she’s been super drowsy lately and we thought it was just aging. this makes so much sense now.

also, typo: 'drowsy' lol i meant 'drowsy' again. sorry.

Melanie Clark 5.01.2026

the pharmaceutical industry knows this and still pushes opioids like candy. they dont care if your liver is failing as long as you keep buying. its not medical negligence its corporate murder. theyre hiding the metabolite risks because lawsuits are cheaper than reform. the FDA is in their pocket. dont trust any doctor who doesnt mention M3G. theyre paid to look away.

also why is this article so long no one reads this shit anyway

Venkataramanan Viswanathan 5.01.2026

in India, many patients with hepatitis C are given morphine without dose adjustment. doctors assume all pain meds are the same. this is dangerous and common. we need better training for rural practitioners. also, buprenorphine patches are rarely available here due to cost and stigma. this article should be translated into Hindi and Tamil.

thank you for writing this.

Mukesh Pareek 5.01.2026

the pharmacokinetic alterations in hepatic impairment are profound, particularly in phase I and phase II metabolism. the reduced hepatic extraction ratio and diminished first-pass effect lead to increased bioavailability and prolonged half-life of opioids, resulting in accumulation. CYP3A4 downregulation in NAFLD is well-documented in hepatology literature, and this directly correlates with elevated plasma concentrations of oxycodone and fentanyl. the clinical implication is non-linear dose-response curves, which necessitate TDM. without therapeutic drug monitoring, you're essentially guessing.

Brian Anaz 5.01.2026

so let me get this straight. we're supposed to treat pain worse just because someone's liver is messed up? what's next, no insulin for diabetics because they're fat? this is just another way to deny people relief. if you're sick, you get meds. period. stop overthinking it. the government and big pharma are just trying to scare us into using less painkillers so they can save money.

also i hate when people say 'transdermal' like it's magic. it's just a patch.

Molly McLane 5.01.2026

thank you for this. i'm a nurse and i've seen too many patients get confused and nearly stop breathing after a routine dose. this isn't about being careful-it's about being smart.

if you're on opioids and have liver issues, ask for buprenorphine. it's safer. don't be embarrassed to ask. your doctor might not know either. we all need to learn this.

also, non-opioid options like gabapentin or acupuncture? totally worth trying. you don't have to suffer alone.

Joann Absi 5.01.2026

OMG this is literally the plot of a Netflix documentary 😭💀

imagine your liver just... giving up on opioids like they're bad exes

and then the metabolites turn into little brain monsters 🧠👻

why is no one talking about this??

also i just googled M3G and now i'm scared to take ibuprofen

send help or at least a meme

Ashley S 5.01.2026

why are we even giving opioids to people with liver disease? just let them suffer. it's their fault anyway for drinking or being obese. if you can't take care of your body, you shouldn't get pain relief. this article is just enabling bad choices.

Rachel Wermager 5.01.2026

the CYP2D6 polymorphism interaction with hepatic impairment creates a pharmacogenomic nightmare. individuals who are ultra-rapid metabolizers of oxycodone will paradoxically experience higher toxicity in cirrhosis due to metabolite accumulation, while poor metabolizers may have subtherapeutic analgesia. this necessitates genotyping before initiation, which is rarely done outside academic centers. the lack of standardized guidelines reflects systemic underinvestment in clinical pharmacology. we need FDA-mandated pharmacogenomic labeling for all opioids in liver disease populations.